Weaver's Week 2019-02-24

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

What is a record?

Contents |

Countdown

The Road to 151

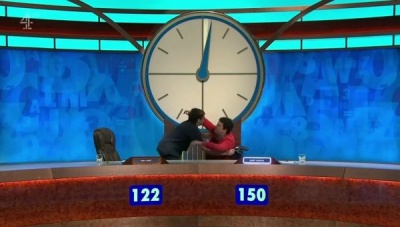

There was much cheering and whooping last month, when Zarte Siempre set a one-show record for Countdown. 150 points in a single show. A truly monumental achievement, and one we think will last for a very long time.

But how long? When will we next have cause to say "Yes, a record is a scramble of idocraser, but that's a mass noun and can't have an agent form!"? We can't say for certain, but we can make an estimate based on statistics.

Countdown evolves and mutates over the years. The current show structure (10 letters rounds, 4 numbers choices, one conundrum) emerged in early 2013. Changes to the dictionary came about in summer 2014, a somewhat larger word list than previously available, and one regularly updated. To provide a reasonably consistent sample, we're going to look at shows from series 71 in June 2014 to the end of series 79 last December.

Why do we care about the dictionary? It's where the variance in a game happens. The conundrum is always going to be worth 10 points. The best solutions to the numbers games will almost always yield 37 or 40 points – research{a} shows that over 91% of numbers games can be solved precisely.

The letters are much more variable, and cause much larger swings in the score. Taken in isolation, at least 5.6% of letters rounds contain a nine-letter word. Another 34.6% of rounds contain an eight-letter word, and 43.4% top out at a a seven-letter word.{b} Countdown scores at one point per letter – 7 for a seven-letter word, 8 for an eight-letter word. Nine-letter words get a bonus, and are worth 18 points.

That's the big difference – one extra letter boosts the possible score by ten points. A set of rounds with four nine-letter words will be worth so much more than a set of rounds with one nine-letter word.

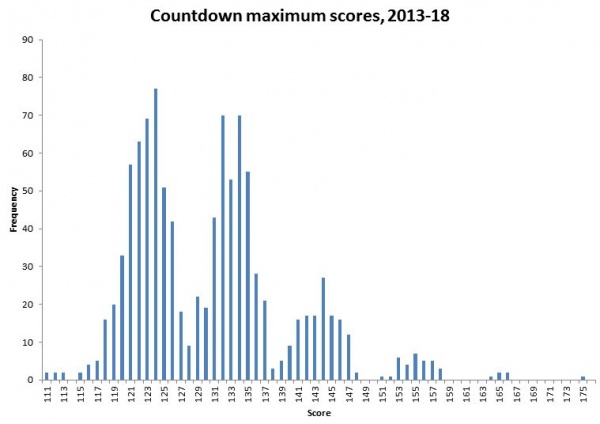

We can approach this question in two ways: from probability, or from observation. Let's do the observation first. The maximum possible score for each show is calculated by the Apterous project, and we can make a graph of each show's maximum.

Clearly, it's uncommon for a show to have a maximum of 150 or more. 38 shows out of our 1032 episode sample allowed 150 points, roughly one show in 27. So the record can be beaten.

A Monte Carlo model

Or we can approach the problem through statistics. Assuming that all letters rounds are independent events{c}, we can model the outcome of each round (letters – and numbers, while we're at it), and work out how many games have a certain maximum score.

And here, we find there are more niners than before. Data from the June to December 2018 series shows a significant shift. The proportion of rounds maxing at 6 letters or less has fallen from 16.5% to 13.0%; the proportion with nothing better than a 7 has fallen from 59.8% to 51.3%.

Most crucially, the percentage of rounds where a nine-letter word is available has increased from 5.7% to 9.3%. With bonus points for a niner, that increases the availability of hyperscores.

In a process known as "Monte Carlo modelling", we set the UKGameshows computer Mr. Babbage away to make up 100,000 hypothetical episodes of Countdown. Assign the score to each round, based on the probabilities we've found, and add them up. We did this for each round without considering others on the show. By the time it had finished this run, Mr. Babbage had independently derived the teapot, a central clock, and Jeff Stelling.

We find the median show has an average of 127. Even with perfect play, half of the shows score no more than 127. A score of 140 will appear once in 7.6 shows, so an octochamp playing perfect games every time should record a score this high. (By-the-by, a perfect player's octochamp run will total 1000 or more in about 90% of our trials: that mark might be the ultimate in sustained Countdown excellence.)

Note the lumps in the distribution – lots of shows have maximums in the low 120s, lots in the low 130s, but very few around 128 or 138. These reflect the bonus awarded for each 9-letter word – no niners will cluster in the low 120s, a single niner will cluster in the low 130s, two niners will cluster in the low 140s.

Zarte's score of 150 is unusual, it appears by chance slightly less than once every 40 shows. A Champion of Champions playing perfectly will win 15 games, and might not have a chance of equalling the record. Two Champion of Champions candidates playing perfectly will win 28 games and tie one more, and it's likely that one of them will reach the mythic 150.{d}

Not every player achieves perfection, and to break Zarte's mark, we might have to go higher. A maximum of 160 points appears every 349 episodes, so about once every year and a half. The maximum of 168 we saw last month is vanishingly rare, about once every ten years by pure chance.

Sidebar: an earlier Countdown format

From September 2001 until March 2013, Countdown had a very slightly different balance, with one extra letters round and one fewer numbers round. Does this make it more or less likely to break 150? We set Mr. Babbage off to watch another 100,000 hypothetical episodes of Countdown. It came up with Jo Brand and Phil Hammond, and started work on a creature it called Gyles Bran. We're now scared to ask it to do any more work.

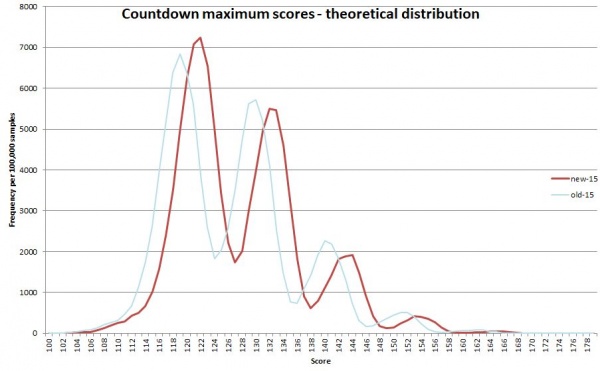

Shifting just one round makes a difference to the maximum score: rather than a near-guaranteed 10 points, we're offering a 93% chance of slightly fewer points, and a 7% chance of many more. There are fewer games with very low maximum scores – every letters round has some points, some numbers rounds are pointless endeavours.

But for the bulk of games, the maximum is depressed. The median game drops from 127 to 126 points, and your average octochamp will max at 139 rather than 140. (That 1000-point octochamp run? About a 75% chance.)

As we reach elevated scores, the bonus from an extra letters game kicks in. The chance of a 150-point game increases from 2.45% to 2.62%. That's a change from once every 40 shows to once every 38 shows. A 160-point game returns every 247 shows, not every 321 – every fifteen months, not every year and a half. It was easier to reach a maximum of around 150 under the old arrangements.

The change from "old-15" to "new-15" increased overall scores by a couple of points, and reduced variance – the no-niners peak on the graph is higher, because there's one less letters round to find a niner.

In conclusion

Not every player is as good as Zarte Siempre. 151 points and more may be on the table, but it'll take someone with an encyclopaedic knowledge of the dictionary – and the bravado to offer some outlandish words – to convert the maximum into points. Basically, it'll take a superb player.

The record of 150 points was a combination of remarkable factors:

- A game where 150 points were available. Half of the Champions of Champions will never see one of those, ever.

- A player of exceptional talent and bravery. Most shows with 150 on offer aren't played by potential series champions.

- And the element we've taken for granted – a show that lasts long enough to make these records worth noting. Thirty-six years of Countdown, about half of them in a 15-round format. We might have asked Mr. Babbage to watch 200,000 made-up episodes of Countdown, but the production staff have actually made 7000 real episodes. That is a record and an achievement in its own right.

Zarte's score will stand for a long time. In the fullness of time, perhaps long after this column has crumbled to digital dust, some young challenger will eclipse him; records are made to be broken. The brilliant performance, and the Championship of Champions, these will never be erased.

Footnotes

A good academic paper needs footnotes. In a vain effort to come across as academic, here are our footnotes.

{a} See http://doc.gold.ac.uk/aisb50/AISB50-S02/AISB50-S2-Colton-paper.pdf Back!

{b} Research by Graeme Cole on C4Countdown, February 2013. Back!

{c} We know this assumption isn't true, as the pile of letters isn't replaced during an edition – once the Q has come out, it won't appear again until tomorrow's show. A proper model would take this into account, and consider letter distribution from round to round.{e}

{d} By random generation of each round, there's one 150-pointer in 40 games; from observation, there's one 150-pointer in 28 games. This does emphasise the slight deficiencies in our model. Back!

{e} A really good model would also consider the optimal strategy for picking the final letters in each round given the first selections. Such a project would be computationally massive and requires expensive brownian motion generators beyond this column's ability. Now, this tea's gone cold... Back!

University Challenge Update

University Challenge has begun its group phase, the extended method of reducing eight teams to four via a double-elimination tournament. No-one advances to the semis from these matches, and no-one leaves the contest.

Glasgow played Durham in the opening fixture, and Durham looked like the form team after two strong wins. The Macaroni Penguin made its annual appearance, as did records by Marian Anderson. Durham took a few minutes to get into gear, and didn't dominate the buzzer race as we'd seen them do; Glasgow lost the match on the bounses, converting less than one per set. The result was a 170-110 win for Durham.

Darwin Cambridge and Bristol met in the second match. A low-scoring affair, with Darwin captain Jason Golfinos not as hot on the buzzers as he'd been earlier, and neither side covering themselves in bonus round glory. The result: 105-105, a draw. University Challenge doesn't tolerate draws (that'll be the College Bowl roots), and the teams began a prolonged series of tie-break starters. Five in all were asked, with Bristol eventually giving the correct answer to progress to the winners' bracket.

Manchester The Team Everyone Wants To Beat met quarter-final regulars Edinburgh. It was a match of three parts: Edinburgh sprinted ahead with knowledge of Baghdad and Ladybird books. Manchester responded with Schopenhauer and multiply-medalled athletes, and briefly held the lead. Anish Kapoor gave bonuses to Edinburgh, Manchester didn't know about binary arithmetic, and Edinburgh ended up 170-130 winners. The bonus rate – two out of three across the game – proved the difference.

Emmanuel Cambridge played St Edmund Hall Oxford in the final match. St Edmund Hall won it by 190-55, entirely thanks to Freddie Leo and his 11 (ELEVEN) starters. Mondegreens and actors who played Heathcliff passed through the show, but there was only one star.

Winners and losers meet in some quarter-finals and elimination matches, and we'll report back in a month.

This Week and Next

Taskmaster is up to series 8, and the competitors have been named. Joe Thomas from The Inbetweeners, The Fabulous Iain Stirling from The Dog Ate My Homework, Lou Sanders from a stand-up stage near you, Paul Sinha from Fighting Talk, and Sian Gibson from Car Share with Peter Kay. That'll be on UKTV Dave later in the year.

BARB ratings in the week to 10 February.

- Call the Midwife is still the most popular show (BBC1, Sun, 9.05m). Dancing on Ice the top game (ITV, Sun, 6.2m).

- The Voice comes second (ITV, Sat, 5.55m), and Pointless Celebrities takes bronze (BBC1, Sat, 4.8m). Just behind come The Chase (ITV, Fri, 4.3m) and The Greatest Dancer (BBC1, Sat, 4.1m).

- On ITV, This Time Next Year (Tue, 3.4m) and Brightest Family (Wed, 3.35m) do well for midweek. Less impressive scores for Through the Keyhole (ITV, Sat, 2.5m) and Small Fortune (ITV, Sat, 2.4m) – the latter is down a million on last week.

- Only Connect still leads on BBC2 (Mon, 2.4m), ahead of University Challenge (Mon, 2.3m). Hunted was Channel 4's top game (Thu, 2.2m). Eurovision You Decide had 1.25m (BBC2, Fri).

- Top game show on the digital channels was Shipwrecked (E4, Mon, 640,000), followed by Hell's Kitchen (ITV2, Wed, 570,000) and A League of Their Own (The Satellite Channel, Thu, 500,000). Dave's new show Hypothetical arrived with a strong 475,000 (Wed).

Two new-ish shows for Wednesday. Your Face or Mine returns (Comedy Central) with Oti Mabuse. Project Z (CITV) translates the Welsh-language hit show into English. The Hangover Games (E4, Tue) is a competition of drinking and drinking.

Welsh-language song contest Can i Gymru is 50 this year. There's a documentary about the competition's cultural impact (S4C, Thu) ahead of the 2019 contest (Fri).

Next Saturday has the return of !mpossible Celebrities with Shaun Ryder, and All Together Now with Rob Beckett.

New television channel BBC Scotland launches this week. It promises a distinctly Caledonian schedule, including The Nine O'Clock News, soap opera River City, and topical debate-and-gunge programme Question Mc. There are games as well.

Test Drive (weeknights) has three teams competing to reach a mystery destination. Their satnav asks questions, and incorrect answers will divert the cars from the shortest route.

Breaking the News (Friday) is a television version of Radio Scotland's much-heard quiz about the news. Susan Calman, Rory Bremner, Tiffany Stevenson, and Stuart Mitchell form this week's The Panel. We look forward to seeing it.

Photo credits: YTV, France Televisions.

To have Weaver's Week emailed to you on publication day, receive our exclusive TV roundup of the game shows in the week ahead, and chat to other ukgameshows.com readers, sign up to our Yahoo! Group.