Weaver's Week 2009-09-13

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

We regret to report the death this week of Mike Bongiorno, the Italian quiz show host. Known for his catchphrase of "Allegria!", Bongiorno appeared on RAI Television on its first night, and hosted local versions of game shows – including the 64 Million Lira Question and Wheel of Fortune – for over twenty years. He was the subject of a learned paper by the philosopher Umberto Eco. Bongiorno continued to work until his death at the age of 85.

Contents |

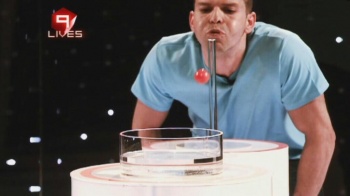

The Cube

Objective Productions for ITV, Saturday nights from 22 August

| Based on an original idea in the Election Night Armistice, we've spent much of the summer constructing the Format Tombola. What we've got is four wheels: a dozen basic ideas, a dozen settings, a dozen interchangeable hosts, and a dozen defining twists, and we'll spin each wheel and try and come up with a viable format out of what emerges. It's fun for literally some of the whole family.

While we were trying the Format Tombola out, we rigged it to always stop on "observation", "outdoors", "Bill Bailey", "watch the birdie". Someone at West London broadcaster SKY television must have heard us, because they've commissioned a series where Mr. Bailey will take people to nature reserves in West London, and invite them to film wild animals while dodging the big metal birds flying into Heathrow. So, let's spin the Format Tombola and see what comes up. "Easy games." "Confined space." "Phillip Schofield." The Crystal Maze revival, anyone... What's the defining twist? "Spewsome special effects." That's going to make it awfully difficult to review, seeing as how we'll have to keep a sick-bag handy. | |

| Anyway, the billed star of the show is going to be a familiar face or six. No, Phillip Schofield, none of them are yours; even though we've been fans ever since you were Gordon the Gopher's left-hand man, there's a bigger star in the show. We speak, of course, of the cube from 19 Keys, that ever-so-simple daily quiz in which Richard Bacon invited people to guess which of nineteen keys opened a box containing money. Just because young Mr. Bacon didn't understand the rules...

Since 19 Keys last graced our screens in 2004, the cube has been lurking in its mountaintop eyrie, waiting for its chance to burst onto the nation's screens again. It almost came back last year, when this show was piloted for Channel 4 with Justin Lee Collins hosting. That would have been an error. The central conceit of The Cube is that players – and only one person plays at a time – are asked to do some simple things — in the cube. They are invited, for instance, to throw a basketball into a bucket while standing on an oversized record player — in the cube. Or to blow a ping-pong ball into a beaker of water — in the cube. Or to walk in a straight line while wearing the Helmet of Justice — in the cube. Or to retrieve the Used Snotrag of Invisibility without disturbing the Custard of St Olive — in the cube. Or to make a cup of tea — in the cube. | |

| You get the idea. Mr. Schofield presents the challenges as being entirely simple, but he is being more than a little disingenuous. It's actually quite difficult to walk along a narrow path while sightless, or to throw a basketball into a bucket while spinning. These are games that, with a bit of dressing up, wouldn't have been entirely out of place on The Crystal Maze. Indeed, such challenges as moving a box across the floor without disturbing it were certainly offered by mazemasters O'Brien and Tudor-Pole. If entered on The Crystal Maze, we reckon the vast majority of challenges would have been classed "skill" or "mystery" – there's usually a "mental" test in there, but the restricted dimensions of the playing area mean there can't be a "physical" challenge.

This being ITV, we're not going to be playing for time crystals or a weekend rock-climbing in the Dales. No, we'll be playing for frugal lucre: cash, and lots of it. There's a thousand pounds for completing the first challenge, and it doubles for the second success. Then the prizes ramp up: 10 grand, 20, 50, 100, and a top prize of £250,000. Such an achievement may look impossible, but we're in no doubt that someone will be challenging for the top prize by the end of the series. | |

| What's to stop everyone from walking off with the top prize? Ah, the show isn't that tolerant of failure. Each contender is given nine opportunities to botch the task, after which they'll be knocked out of the programme entirely. What's more, once they accept a challenge, they cannot subsequently withdraw: they must play on until it's won or lost.

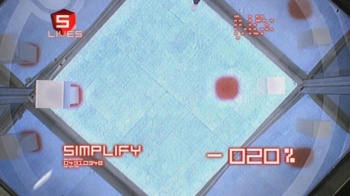

There are a couple of lifelines available – a contestant may make any one game slightly more simple, and they may take an experimental run at any one game before committing to play it. If they win the game, it doesn't count; if they make a monkey fist of the run, it won't hurt them, they can still take the money and run. The basic game, therefore, is a sequence of take-it-or-leave-it challenges for rapidly increasing amounts of money. To assist the contestant, Mr. Schofield is able to give some facts about how many failures other people took to complete the task, and any significant patterns that emerged – shorter people are better at some tasks than others. Inevitably, there's false tension introduced from time to time – "will she go for it? Find out after the break." The first few shows were all complete in themselves, featuring two contestants whose games were both finished in the hour. We're reminded of how One Versus One Hundred went halfway through its first series before introducing rollover contestants. | |

| All of this, of course, is to ignore the elephant in the room, or rather the cube in the studio. The Cube is given mythical powers, as though it were the most evil creation in the entire history of creation, making Waramonga, the ancient goddess of war-mongers, turn blue with envy. It's set up as a totem of challenge, and given a gruff voice – that of actor Colin MacFarlane – to beguile the contestant while saying that this isn't going to be easy. "All you've got to do, Jimmy, is pot the three red balls, and you've four lives left, Jimmy." Oh, and it calls the contestant by their name a lot.

As we've already discussed, the games think they're all that easy to begin with, but they're not, and contestants will lose lives as they go on. From time to time, the rules aren't explained particularly well to the audience at home – the contestant throwing a basketball from the record player into a bucket was failed on one attempt for bouncing the ball off the wall of the cube. Indeed, the reaction of the studio audience suggests that this wasn't explained well enough to them, either. Other games require the contestant to use the walls as reflective surfaces. Both are valid rule, but they've got to be clear and they've got to be consistent. If the game's being done in the cube, should it exploit the cubular nature of the cube: to wit, that it has six faces, at least five of them transparent? Is the roof, is the wall part of the playing surface or not? This is never properly resolved. | |

| To add to the seduction, there's a filmed demonstration of just how easy these games are. They're shown by The Body, a woman clad in white and wearing a fencing mask. She comes on, does the game, wins the game, and leaves in a green mist. Hikka-bikka-boo, it's that easy. Of course, the contestant isn't shown the many tries that she took before completing the game. That would spoil the illusion.

So would the cameramen appearing in shot. They're there, and if you look at still photos, they're clearly visible, but in the heat of the programme, and because it's only lit from within, the cameramen are able to get very close to the wall of the cube and not appear in shot. We reckon there are at least eight cameras around the cube, close enough to pretend to be in there with the contestant. According to the publicity, The Cube has "state-of-the-art filming techniques". This amounts to slowing down the playback and digitally enhancing the footage so that it looks like there are cameras at every possible angle. Other than recaps after the commercial breaks, there's not a single replay in the whole programme. This has some tremendous drawbacks: in games that are decided by only a small margin (such as put balls back in a jar — in the cube) the viewer is denied a chance to check the producer's decision was correct. Nevertheless, all these effects mean the show looks a million dollars. | |

| The show looks a million dollars, but we're not sure if they're loonies, kiwis, or Zimbabwean. We found ourselves watching the reflections more than the action, looking for dimly-lit camera lenses. Why did we do this and zone out of the action? Quite simply, we found ourselves reaching for the sickbag after about ten minutes. The dominant colours in The Cube are red, white, and black. As we've found to our cost while watching White Stripes pop videos, that combination has us barfin' and barkin' after just a few minutes. And that's before the contestants remove their jeans so that they might gain extra mobility when attempting to clear some high hurdles.

This is a shame, because the set design is entirely coherent. The floor of the cube is white, with red shadows where fixed objects (boxes, poles) touch the ground. All the balls are red, all the props are white, red, or transparent according to the game. The backdrop is always black, with just the softest of lighting bringing out the contestant's friends and family in the audience. And there's a rotating pathway, going from the circle where Mr. Schofield stands to the back of the studio, and then turning to meet the cube. It is unfortunate that this column cannot watch The Cube for more than ten minutes at a time. We like the idea, even if the whole Evil Cube thing is tremendously overdone, and the challenges are made out to be a bit more simple than they objectively are. A little hype never dragged anyone down. Phillip Schofield is, as usual, the quality host, not putting any pressure on the contestants to play, giving them sensible and balanced advice throughout. But no show is worth us worrying about seeing our dinner again, and the aesthetics mean we'll have to bow out after one episode to review, and taking a very careful look (small screen in the corner of our computer) at another contestant to provide pictures. |

In the Thursday television guide, we asked this question, in the style of Round Britain Quiz. "A physician of Ephasus; the son of the bastard who waltzed Matilda; and a drawing of Heterocephalus glaber. Why does the red man from 2688 bring these wild stallions together?" Answer later.

University Challenge

Heat 9: Imperial College v Southampton

| The opening question is Timeframe of the Week: its "every ten years", and it's answered by Imperial College. Thumper is correct to remind us that the institution is no longer part of the University of London, having declared its independence in 2007. Alumni include Alexander Fleming and HG Wells, while Brian May of Queen left part-way through his course.

Southampton get the next starter, on paradoxes. This institution was founded in 1850 by a wine merchant, who thought he was getting an institution for the betterment of the people of the area. Who said he wasn't? With this slur, and the claim that "taxpayers will find out whether their money is well-spent", we wonder if we've tuned into The Daily Hell channel. Anyway, famous alumni include the original webmaster Tim Berners-Lee, top sportsbod John Inverdale, and KP from Bother's Bar. Thumper asks a bunch of questions about the only surviving member of various classes in fauna and flora. He doesn't know what he's on about, and neither does the Imperial team. They get the visual bonuses, on anagrams of historical figures, and Imperial leads 60-10. We'll take Good Question of the Week:

| |

| Why is this a good question? If someone knows the answer, they can get it half-way through, the answer is obvious by the end, and there isn't the terrible swerve that so dogged the quiz earlier in the decade. Imperial prove themselves experts on the Arabian peninsula. We feel that we ought to explain the -UMA question, because the show didn't. The city in Western Arizona, successor of Romulus, lower house of Russian parliament, and another name for a cougar are (respectively) Yuma, Numa, Duma, and Puma.

Clear? We'll move on, and after some bonuses on centuries, we reach the audio round. It's questions on Synth Pop Circa 1980, and Imperial has a large lead, 120-35. There's a question on objects with descending numbers of faces, diminishing from a cuboid (six) to a cricket bat (one). Southampton get a set of bonuses on ships, but can honestly say they know nothing about the navy. "That's why we went to Southampton", replies captain Stuart Wynn with refreshing honesty. Yes, if they wanted to know about sailing, they would have gone to Portsmouth. After a short third stanza, we're up to the visual round, on winners of the Best Actor AMPAS award for portrayals of real people. Imperial leads, 155-45. Southampton proves its knowledge of the city of Rome is as good as its knowledge of sailing ships; Imperial prove they know everything about the football world cup. Southampton get modern art for their next set of bonuses, and do only slightly better. With five minutes until that new show on BBC3, it's clear that Imperial has the game in the bag, and Southampton needs to double its score in order to make the repechage board. The rubber feels as good as dead, even though Mr. Wynn is doing his best to drag his side up. He remembers the Latin name for radishes, so he'll be welcome on Fraggle Rock. | |

| And just when we say that, Southampton get their fifth starter in a row, and they're suddenly back in contention. Then they get nothing from another set of bonuses, and it feels like they'll never make it. They don't, though they had us worried for a moment there. Imperial won the game, 175-135.

Very much a game of two parts: Imperial dominated the first three-quarters, then almost seemed to switch off once the game was won. Southampton was never in the running until the final six minutes, then got six starters – and just six bonuses. Gilad Amit gets our nod as best buzzer for Imperial, four starters and just one missignal; his side made 19/30 bonuses and had four missignals – that's more than any other side this year. Stuart Wynn had six of Southampton's starters, the side was right on 9/26 bonuses. Next match: St John's Oxford v Durham | Repechage standings:

|

Mastermind

Heat 3

Yes, this opening really does drag, but then the end of the show speeds away at a rate of knots. Lose on the swings, win on the roundabouts, and perhaps it works better now.

Anyway, Lisa Hermann is discussing the George Cross, a medal created by George VI for extreme bravery. There are a lot of questions on individual recipients, interspersed with questions about other medals for gallantry. It's a tricky subject to pitch questions for, and that was a good set. And a good set of responses: 14 (1).

David Porch will tell us about The Ascent of Man, a television series that told of the story of science, from banging the rocks together to create fire right up to the science that took man off the planet. Jacob Bronowski's landmark series went out in 1973; unlike a certain other series of that era, it's not shown thirty-one times a year, or even once a decade, and we are significantly poorer for that omission. 10 (0).

Ian Orriss has the First Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. This was a city-state founded by the Crusaders in 1099; its precarious existence finally ended in 1291 after defeat by the Mamelukes. We're not entirely sure where the line between the First and any Subsequent Kingdom lies, but we're entirely sure what to make of the round – 16 (1) is a superb score.

Les Morrell concludes, and he'll tell us about Clement Attlee of Stepney, the prime minister of the UK from 1945 to 1951. He's a graduate of University College Oxford, nationalised the Bank of England, and suffered the resignation of the next Labour PM, Harold Wilson. It's another superb score, 16 (0).

So Mr. Porch has something of a mountain to climb, six behind after his opening round. Though he begins with a correct answer, and remembers The Thruppeny Opera, further points are rather difficult to come by, and the final score is 16 (2).

Lisa Hermann starts off with a question about CBBC's most popular sci-fi show about a man who travels through time in a telephone box, Bill 'N' Ted's Excellent Adventure. She's later asked to remember the song recorded by last year's Simon Cowell Annoys finalists; it's since become the %National% Idol calling card, with versions from the Netherlands to Estonia. The final score of 20 (3) doesn't feel like a winner.

Mr. Orriss goes one, two, three, and looks absolutely certain to take the lead. But then the road suddenly takes a rocky turn, with two wrong answers and a pass. Only then can he make progress towards the 26 needed to head the repechage board, or probably win the show. In both rounds, he's lucky to have a question start just before the buzzer, and ends on 27 (4).

Mr. Morrell requires eleven to win, twelve to be sure. He's answering the questions as quickly and concisely as possible, and – unlike Dr. Bayley in the final last year – is doing so exactly in sync with the host. Though the contender gets many right, including the oats in flapjack, he doesn't remember the magician turned president of Gabon (Ali Bongo), and ends on 26 (3).

A narrow loss, but Mr. Morrell will go onto the repechage board when it's full in three editions.

This Week And Next

Results from the Most Popular Television awards, sponsored by H Bauer's listings mags, gave nods to three game shows. Deal or No Deal was Most Popular Game Show, albeit from a listing that didn't feature the UKGameshows defending champion Only Connect. Antan Dec's Saturday Night Takeaway was Most Popular Entertainment Show, and the organisers gave an Outstanding Contribution to the host, not least for their groundbreaking recording career. Psyche.

Perhaps the easiest way into the RBQ-style question was "the son of the bastard who waltzed Matilda". That's a reference to William the Conqueror, the son of unmarried parents who married Matilda; their son was William Rufus. Another Rufus was one of the famed physicians of Ephasus, and fans of the cartoon Kim Possible will recall Rufus the naked mole rat (Heterocephalus glaber). Rufus was also a character in the film Bill 'n' Ted's Excellent Adventure, travelling back in time from 2688 to keep together the band Wyld Stallyns. The name "Rufus" means red, ruddy, rosy.

In the week to 30 August, BARB viewing figures show Simon Cowell Annoys had 10.8m seeing the Saturday broadcast. The Cube came second, 5.1m saw the bloke lose his trousers, and Dragons' Den had a year's best 4.25m. That puts it ahead of Total Wipeout (3.55m) and Shooting Stars (2.95m). University Challenge (2.9m) and Mock the Week (2.6m) both beat Big Brother (2.55m). Mastermind returned with 2m – its most popular show of the year.

Cowell also leads on the digital channels, with 1.4m seeing Xtra Annoying, and 1.06m the Sunday repeat of the main show. Come Dine With Me on More4 claims second place for the week, on 1.18m. Four Weddings continues its remarkable climb, with 730,000 people seeing one of four airings across the UK Living bouquet of channels. The OC had 260,000 on BBC4, and there were respectable numbers seeing Dragons' Den and Shooting Stars on BBC-HD (95,000 and 65,000, respectively).

Next week's Week is a Pointless exercise. Before then, viewers can see a new run of Masterchef The Professionals (BBC2, 8.30 Monday) and Design for Life (BBC2, 9pm Monday). Raven (4.05 Tuesday) and Strictly Come Dancing (8.30 Friday) return to BBC1, and Dragons' Den Online to BBC2 (9.30 Wednesday). New shows include School of Silence (BBC1, 4.05 Monday) and Dating in the Dark (Living, 9pm Wednesday). Four Weddings comes to Virgin1 (8pm Saturday), where BingoLotto also returns (7pm Sunday), and Challenge gains Winning Lines (1pm weekdays).

To have Weaver's Week emailed to you on publication day, receive our exclusive TV roundup of the game shows in the week ahead, and chat to other ukgameshows.com readers sign up to our Yahoo! Group.