Weaver's Week 2009-12-13

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

Contents |

"Is that your identity?"

Weaver's Decade: Part 1: But we don't want to give you that! | Part 2: Who should be voted off the team? | Part 3: Big Brother House, this is Davina | Part 4: Singing for Survival | Part 5: the rest of the best | Part 6: failures and interactivity

| In the first five parts of this history, we've been reviewing shows that have made a mark. Some of them have been astounding, some of them have been spectacular, some of them have been popular, some of them have defined television in this decade, and a few have been all of the above. All of them have one thing in common: the general consensus is that they are remembered with affection, someone thinks the show was worth while. This part of our review of the decade looks at those shows without any defenders, and asks if there's any redeeming feature at all.

Touch the Truck (C5, 2001) has gone down as one of the most worthless pieces of television ever made. Twenty people were challenged to keep their hands on a large vehicle, and Dale Winton presented nightly updates from Thurrock. It was an entirely bizarre spectacle, and one that hasn't been repeated. The programme has become a cliche of the worst kind, trotted out at every opportunity to say "Look at this! It's rubbish!", and that shows more about the lazy standard of research than the programme's poor quality. It was a grand television experiment, and sometimes experiments don't work. Channel 5 said that there was a chance their spectacle might fail. Not so Channel 4, who launched Boys and Girls (2003) as the great return of Chris Evans, fresh from his sabbatical year with Ickle Billie Piper. The only trouble with Boys and Girls was that it was rubbish: the Saturday show meandered along in a manner both dull and unsettling, and swiftly degenerated into a beauty contest. There was an entirely decent shopping challenge for the winner and their chosen companion, but the dramatic tension was undermined by an entirely random end game. Everything about this show was wrong – they even asked Dannii Minogue to entertain the audience by singing, something she's never done before, and didn't do on that show. There was no evidence of the programme's reported budget of half a million quid per episode, and it sank deeper and deeper into late night oblivion before being put out of its misery. |

|

| Unanimous (C4, 2006) also had great hopes, great hype, and completely failed to live up to its billing. Take nine people, wave a million quid under their noses, and ask them to decide who should win the dough. Then, when they can't decide within five minutes, start reducing the prize and the number of eligible contenders until they do give a result. There were many technical flaws in the programme's presentation – endless "coming up / you've already seen" bits around the breaks, getting the contestants to do their own voiceovers – but the main problem was that the show was just dull. The setting was tedious, the characters failed to catch the imagination, and the viewers found they had better things to do of a Friday night. Ratings were so low that we wondered if it might have been cheaper for Channel 4 to send DVDs of the final episodes through the post, rather than broadcast them over the analogue transmitter network.

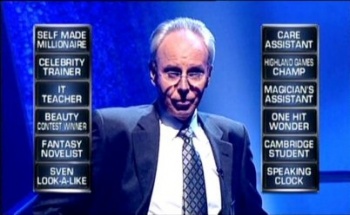

The BBC's not been immune to such ill-conceived shows. Identity (BBC2, 2007-8) asked its contestant to match the person to a one-line description. It was hosted by Donny Osmond, whose career in the 1970s could perhaps be put down to psychedelic madness; his revival in recent years appeared to come from nowhere, and we wish it had stayed there. There was also The National Lottery The People's Quiz (BBC1 and BBC2, 2007), a show so phenomenally unsuccessful that The Lottery Corp. withdrew its sponsorship part-way through the run. The idea wasn't so bad: give people a bus-load of questions and answers to swot up on, hold open auditions, and the cream will rise to the top. But the show tried to be The X Factor, holding Kate Garraway and Myleene Klass to be Quiz Deities, fit to be mentioned in the same breath as William G. Stewart. It was clunky and confusing and had a recurring sexist theme and went on and on and on in a manner that reminded us of the Cricket World Cup – weeks and weeks of meaningless matches before a sudden burst of finals. | |

| But it's ITV that has been the home of the decade's largest stockpile of "Why did we ever let that reach the commissioner's desk?" disasters. The channel became something of a laughing stock in the middle of the decade as it took shows off air at the drop of a hat. Judgement Day (2003, 2 episodes) was a cheap and shallow rip-off of Without Prejudice?. Scream! If You Want to Get Off (2005, 3 episodes) tried to combine wildlife watching with dangerous stunts, and fell between the two stools. For the Rest of Your Life (2007) was a daytime show that wanted to be the new Deal or No Deal, but just sent people to sleep. Tycoon (2007) wanted to be the new Apprentice, but was such a feedback that its final episodes were consigned to the wilderness of ITV4.

Even the digital channels suffered from some particularly bad ideas. Deadline (ITV2, 2007) had celebrities writing a magazine about other celebrities. Again, this might have had some vague merit once upon a time, but the "professionals" set their eyes to the gutter and didn't even get there, the television programme was full of entirely manufactured rows, and the resulting magazine wasn't worth the paper it was printed on. The following year, they tried again with CelebAir, in which very minor celebrities were trained as air stewards and sent on flights to the corners of Europe. Only two things went wrong: they took cameras with them, and these weren't one-way flights. For the first time, the show was panned by the public and mostly ignored. | |

| There's always a place on television for a well-crafted format, even if it's been off air for some years. The Krypton Factor (ITV, 2009 – present) is a perfect example: it's moved with the times and at least made an attempt to remain contemporary. Many of this decade's revivals have been pale shadows of their originals, almost indistinguishable from the shows that pop up on Challenge from time to time. We're thinking of Win Lose or Draw Late (ITV, 2005), a potty-mouthed version of the quick draw show. We think of Going for Gold (Channel 5, 2008-9), twenty minutes of games shoehorned into a 50-minute slot. Superstars (BBC1, 2004-6; Channel 5, 2008) couldn't attract the contemporary sportspeople as it could in the 1970s. Simply the Best (ITV, 2004) was a re-staging of It's a Knockout without anyone laughing at the people doing silly things – the show has to have a Stuart Hall or a Keith Chegwin to laugh at the implausibly silly stuff. And Gladiators (Sky1, 2008-9) was the original show without Wolf, without Ulrika, without Fash, without the Travelator, without the nod-and-wink that it's all a bit silly.

These shows all made it to air for at least part of their run. Press Ganged (ITV, 2004) hasn't even appeared in the listings. Five episodes, five-and-a-half hours, and all that the public knows of it is what we've been able to unearth in our article. They couldn't even manage to sink the ship, as happened on RTÉ's Cabin Fever in 2003. And then there was Infected, which crossed our radar in May 2004. It was a show that appealed for people to get ill, live, on national television, and appeared to be run by Matt Roper, who was then writing for the Daily Mirror. Within a week, a piece appeared in the Daily Mirror, written by Matt Roper, poking fun at people who believe anything they see on television. By a remarkable coincidence, Piers Morgan was fired as editor of the Daily Mirror the same week, after himself being hoaxed. |

"How much can I get for my gum wrapper chain?"

| Back at the beginning of this odyssey, we said that the first game show of the new decade was Millionaire, on 4 September 1998. If you'd asked us that question ten years ago, we would have put the beginning further back, on 30 October 1996. That was the debut of Wanted (Channel 4, 1996-7), a show that was interactive to its core. If the viewers of Wanted didn't call in with their tips and hints, the game of hide and seek would have fizzled out in no time at all. Wanted used telephones, television, theatre-destroying helicopters, and this new-fangled Internet thingummybob to provide live video of two people hiding in a phone box somewhere in London. The programme was exceptionally expensive to produce, with three live outside broadcasts every week, and was quietly dropped after failing to attract a huge enough audience.

Wanted producer Jane Hewland already had experience of interactive television, and experience of interactive television not quite living up to its promise. Watch This Space (Channel 4, 1995) was an entirely interactive youth show, and waved its interactiveness in the viewers' faces. They were asked to select the next week’s features, use video phones to talk with guests, drop into a selected Internet cafe, send faxes, leave messages on the answering machine, send e-mails. The show was highly ambitious, in a way that was far beyond the technology of the mid-90s – the video phones were like staring at an Etch-a-Sketch, the email box overflowed, sending video down the Internet wasn't reliable, and equipment broke down. To no-one's surprise, the show wasn't re-commissioned. Watch This Space invented one phenomenon that would come to define the subsequent decade – that producers couldn't get a telephone vote correct. The show's first edition was hosted by Dominik Diamond so that viewers could televote on who the regular presenters should be. At the end of the programme, lines closed and Diamond read out some results. However, those weren't the actual results, but the fake results that they'd used for the rehearsal, and were written on the back of the actual results. The producers made advantage of their cockup, producing trails along the lines of "See what happens when professionals present programmes? It all goes wrong!" Subsequent scandals would be less primitive than the host reading a script upside down. | |

| Indeed, there had been interactive shows even before this – the BBC's children's department had made annual What's Your Story shows (1988-91), using ideas suggested by the viewing audience. Could we get Tony Robinson to speak our lines on national television? Not necessarily – as with the semi-improvised radio comedy The Masterson Inheritance (Radio 4, 1993-5), What's Your Story took ideas from the public, and wove them into what looked suspiciously like a pre-planned outline plot. We've not paid enough attention to Chain Gang (BBC7, 2009) to work out if the authors are pulling the same trick, and we'll assume they're not.

The problem with interactivity is that it's very labour-intensive. Someone has to read all the submissions, eliminate the obvious nonsense, check the points made, perhaps edit it into other ideas. This is hard work, it's almost impossible to under-estimate how difficult it is. The People Versus (ITV, 2000-2) tried to source its questions to the crowd of viewers, but this might have proven its undoing. Those of us who think The Simpsons is an everyday story of royal paramours won't be able to answer a question asking for Seymour Witham's middle name as revealed in episode 407. Such is the obscure nature of the question, and the slow pace of change, that it can be entirely off-putting to the viewer. Getting people to set general knowledge questions, as they did for the daytime series, was much better, as these can be edited together into a more interesting whole. Perhaps the failure of The People Versus prevented ITV from sticking too closely to the original model of The Vault (2002-4). In Israel, where the show began, contestants have five minutes to complete their run, and viewers can call in to help them out. There's some backstage screening, so the contestant knows that the viewer they're speaking to will give the correct answer, and it becomes a question of negotiation: how much will the contestant pay for a guaranteed correct answer. But that would require lots and lots of switchboard operators all taking calls at the same time, and ITV remembered when they tried that on Talking Telephone Numbers – the whole telephone exchange fell over. Instead, The Vault combined studio brokers (which worked), telephone brokers (which probably didn't), and a totally broken endgame. |

Questions written by the viewers. |

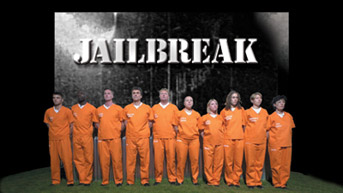

| Reality shows also tried to get properly interactive, with the viewers suggesting things for the contestants to do. Jailbreak (C5, 2000) allowed its inmates to read a certain number of emails each day – we don't recall the detail at this distance, but we think they were screened by the producers to ensure they were worth reading, if not necessarily helpful or accurate. Eden (C4, 2002) took this a step further, promising to make the viewer a Proper God of reality shows. We remarked at the time that the viewer wasn't allowed to be a very powerful god, restricted to a menu of options that the producers were happy to make.

We didn't realise that Eden was setting the limit of our power for the remainder of the decade. Viewers would be allowed to determine who to vote out, who to vote through, who should sing some more and who should shut up, but we wouldn't be able to tinker with the rules of the game at all. That power was retained by the producers, who let the viewers have scraps from their table. We'd been given the scent of power, we'd been allowed the chance of setting the agenda in the mid-90s, and that was now being snatched away from us. Even Big Brother's Little Brother was complicit in the process: it was a different sort of television programme, where the viewers could suggest the detail, but the broad brush strokes were still decided by Dermot and his producers. Yes, it made for excellent television, but it wasn't truly interactive. As the decade progressed, it became clear that the television producers weren't going to allow the viewer to gain the upper hand again. It was too expensive for them to do it properly, so they weren't going to bother. Well, they weren't going to bother unless we paid for the privilege, on call-and-lose competitions along the lines of "Guess what number I'm thinking of." The growth of Super Ceefax and other "red-button" thingummies helped to contain viewers' expectations. Crisis Command (BBC, 2003-4) offered a very limited interactivity, restricting the viewers to the options available to the cabinet ministers on the show. Want to evacuate a mile around a hospital where there are cases of the plague? It's a plausible response, it's not a scenario the producers wanted to consider, so it's not on the table. | |

| As one example, Deadline, the celebrity celebrity magazine show, could have done so much more with its readers: let them email their criticisms, tell the staff what worked and what failed, give genuine feedback from genuine readers to Darryn and Janet. Instead, the professionals were treated as gods who were above criticism. Even their haircut was not to be criticised.

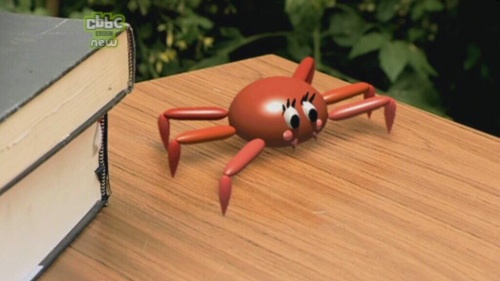

Has any new show met our high standard of interactivity, where the viewers have a big part to play in determining the outcome of events? When we first drafted this article, back in the summer, we answered in the negative. Then Bamzooki (CBBC, 2004-6, 2009 – present) came back, and we found ourselves answering in the positive. Here's a Properly Interactive show: the viewers design their own battle monsters, some of them come to the studio where they're put through their paces in defined tests, and the winner wins. Without viewer participation, the show cannot exist, and that's our touchstone for a properly Interactive (with a capital I) programme. Where television has given up, the theatre has jumped in. There's been a huge growth in immersive theatre over recent years, shows where the actors address the audience directly, sometimes where the actors and audience intermingle. Some of these shows can be classed as game shows in a theatre. This column saw Everybody Loves a Winner in Manchester over the summer. In this show, the theatre – audience, actors, even some of the ushers – all played a real game of bingo, for real cash prizes, live on stage. Audiences could interpret it as a reflection on society's value for money, on how people are meant to know the price of everything and the value of less. Audiences could interpret it as a message to chase their dreams, to make whatever difference was in their power. They could use it as a chance to explore the motivation of people with more time and less cash than themselves, on why people expect forces outside their control to shape their lives. Only those who expected great character development – or who believed they had a divine right to win the bingo – came away disappointed. Theatre's also given us We Need Answers (Edinburgh 2007-8, BBC4 2009 – present), in which the public set the questions, they're selected for style and content, and then asked again of famous people, comedians, or famous comedians. It's The People Versus with a less funky set. Who Wants to Be... is a spin-off from Millionaire, in which the audience is asked what they want to do with the night's box office takings. Splurge it on ice cream for everyone? Use it to buy dynamite and blow up the council office? Donate it to a proper good cause? One of the UKGS team has seen the show, and we cannot explain the phenomenon half as well as he does. | |

| There are already touring versions of some radio comedies – I'm Sorry I Haven't a Clue regularly sells out theatres across the land, Just a Minute spent much of the decade out and about until budget cuts forced it to shelter in London. Could harder quizzes travel the land – might all-comers be invited to Beat the Eggheads? Could the best contestants of the night take part in a Number One revival, for that show (C4, 2001) had movement, drama, and a sense that no-one was truly out until the final few moments.

For the bulk of the decade, this column has been chronicling game shows. We've worked out what we like, we've railed against what we don't like, we've tried to judge everything on its merits. This column has found its voice, and a voice is in a written form that can be emailed, printed, and discussed. But it's only a small part of a greater picture – there has always been more to the world of game shows than this one viewpoint. This column is part of a community, and we offer our humble thanks to the community leaders. David Bodycombe, editor of UK Gameshows.com, who has put up with nine years' worth of this stuff. Jenny Turner, who has attempted the Herculean task of editing out the double negatives and over-complex sentences and still hasn't run for the hills. Chris Dickson, who started many balls rolling, some of which we've followed. Nick Gates, whose Bother's Bar site provides daily commentary for everyone who wants information now. But we must also thank the many other contributors who have talked about shows, brought ideas to the table, commented, emailed, read, participated, and otherwise given us something to chew on. This column would be nought without a supportive game show community, and many heartfelt thanks to you all. Where do we go from here? We go further! In recent years, it's become possible for people to make their own game shows, and put the video up on the web for all to see. Some of them are poor, but a gratifyingly large proportion are good. Some of them are astoundingly good. Accumulate! (RUON, 2009 – present) is the best web game show that we've seen – it demonstrates that a great format and outstanding minds can overcome such trivial limitations as not much budget and a set that looks like a prison. If regular television producers don't allow viewers to shape shows as they want, the viewers now have the power to make their own television. This might just be the net result of interactive television: programmes that completely bypass the traditional mass media. This column – or its successor – will have to see what's happened ten years from now. |

University Challenge

Second round, match 5: Jesus Oxford v Warwick

Warwick beat Christ's Cambridge in the opening match of the season, way back on 6 July; Jesus Oxford beat Clare Cambridge three weeks later. Both losing sides made it to the repechage, but lost again in their first match. One of the winners must become the sixth side through to the quarter-final stages.

The opening question is a variation on a theme: name that year. It's 1983, and one of the facts not included was the winners of that year's University Challenge. Jesus get the starter, but don't do too well with a set of bonuses on words that have changed their meaning. Warwick do little better with a series on painters. One starter asks the teams to find a word that rhymes with other clues: we're having difficulty finding enough rhymes for "alligator", and Warwick go on to suggest a small fall of snow is called a "turkey". This show's turning into that episode of Family Fortunes, isn't it?

Euler's Equation gets mentioned, but not fully read out: it's eπi+1=0, combining five of the most important constants in one equation. The first visual round is on the world's tallest structures, beginning with a rather tall hotel in Dubai. And, given the financial crisis hitting the country, it could be yours tonight, if the Price is Right! Warwick's lead is 70-15, and we run into a couple of dropped starters, including one where the teams are unable to define the word "punchdrunk". Once experienced, not to be forgotten.

Jesus do well on questions about long-distance paths, but can't remember that Hadrian's Wall finishes at Wallsend. Maybe they should have given the town a less obscure name. The audio round is on classical choral music, which is all rather lovely, and brings Jesus back into the game, though they still trail 85-75. Knowledge of the buckle smear draws the sides level, and a good guess at a citrus fruit puts Jesus ahead by a nose. It only lasts until the next starter, and Warwick prove rather good at crystal packing. It's almost as if they'd spent their childhood watching people chase them down.

Knowledge of the Runic alphabet puts Jesus back in the game, and ensures that all four contenders have answered at least one starter correctly. But neither side is doing particularly well at the bonus questions: their aggregate bonus conversion rate is barely above 50%. The second visual round asks people to name a famous Belgian painter, which is a contradiction in terms, and Warwick's lead is up to 145-100. Warwick ensure everyone's had a starter with the next question, which gives them more questions on painters they've not heard of. They do better on parts of the ear.

Just when Jesus look to be in dire straits, they come back with knowledge of people who gave their name to diseases. They come back with knowledge of African monarchies, the Routemaster bus, and a question taking forever to ask "what's four cubed"? And on they go, with Roger Tilling showing more signs of needing to let off a bit more steam. Knowledge of ammonia production brings Jesus to within five, but they know nothing about prime numbers. Warwick incur a missignal, Jesus pick up the starter and the lead, and run down the clock while making a decent stab at the questions. But it's not over – another starter, "probability" from Jesus is correct, and that's going to be the game over. Geekery of the Weekery crops up in the final seconds, asking for the expansion of ADSL, and Jesus have another close win, with a score of 200-170.

For Jesus, James Waterson made four starters, all his colleagues had three correct. The team's bonus conversion rate fell away during the second half, ending on 14/39. Matthew Smalley gets the best buzzer nod for Warwick, with four starters and one missignal; the side made 17/30 bonuses and had a total of three incorrect interruptions. With eight dropped starters, the show's overall correct rate was 54/100.

Next match: Edinburgh v Regent's Park Oxford

Then: Manchester v King's College London

This Week And Next

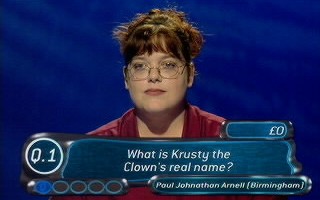

A remarkable edition of Brain of Britain, as Only Connect champion Ian Bayley (pictured) ran his score up, and up, and up some more. By the end of the show, he had a total of 33 points, just two short of the all-time record held by such luminaries as Kevin Ashman. Just so long as there isn't a Mastermind champion in his section of the draw... what's that, David Clark of "Life After Mastermind" fame? You'll be on the show next week? Now we don't know who to cheer for in the semi-final! Mr. Clark's extended review of the show is on his blog, and it's well worth reading.

Police in Australia have been investigating the recent series of I'm a Celebrity... Get Me Out of Here! They said "G'day, g'day, g'day" to Gino D'Acampo and Stuart Manning after the contestants killed and cooked a rat while on the studio set. The two will face criminal charges for animal cruelty, and must attend court on 3 February next year.

Ratings for the week to 29 November have Simon Cowell on 14.3m, a little bit down on the past. I'm a Celeb peaked on Monday with 10.15m seeing Jordan: the flounce-out, with Strictly restricted to 9.75m, plus 200,000 on BBC-HD. Family Fortunes was seen by 6.25m, HIGNFY by 5.1m, and QI returned just shy of 5m. University Challenge continued to power away, 3.5m Thumper-fans tuned in, with 2.75m for Dancing on Two and 2.6m seeing Come Dine With Me.

I'm a Celeb led ITV2's ratings, with 1.23m on Monday night beating Sunday's Cowell show (825,000) and Come Dine With Me (1.01m). Mock the Week on Dave was the next best, with 480,000; America's Next Top Model (360,000) was the leading new game show on the digital tier, closely followed by CBBC's Bamzooki (320,000). But let us pose the great question of our time. Which is cuter: a Top Model contestant or the lovely Mimi?

'Twas the week before the week before Christmas, and all through the schedules, only one programme debuted, and it was a mouse. That's Move Like Michael Jackson (BBC3, from Monday), and there are some sheep, in One Man and His Dog (BBC2, from Tuesday). It's certainly finals week, though: Simon Cowell Annoys reaches its peak of indifference (ITV, Sunday), then there are ends for School of Saatchi (BBC2, Monday), Fferm Ffactor (S4C, Tuesday), Britain's Best Brain (C5, Wednesday), The Restaurant (BBC2, Thursday), Countdown (C4, Friday), and Strictly Come Dancing (BBC1, 6.35 and 8.40 Saturday).

To have Weaver's Week emailed to you on publication day, receive our exclusive TV roundup of the game shows in the week ahead, and chat to other ukgameshows.com readers, sign up to our Yahoo! Group.

Hands on a hardbody with Dale.

Hands on a hardbody with Dale.